Talk About Love

Rev. Dan Schatz

May 14, 2023

Readings:

Mother’s Day is complicated. Joyful for many, yes, but complicated.

It’s right there on the calendar, even if your mother has died. Even if you’ve been told, yet again, that you’re still not pregnant; or if you’ve never been more scared than you are right now because you are pregnant, it’s Mother’s Day. Even if your own mother’s priorities included everything but you, there’s going to be a Mother’s Day google doodle with flowers and pink stuff. Even if you have scars, ones you can see or ones you can’t, it’s Mother’s Day. That cake mix commercial is going to roll out four times an hour even when you can’t stop shaking and crying because you can’t believe [what you said to] your little boy today. It’s Mother’s Day. And we all have to live with that, in those silent, breathless moments, because even when the baby dies, it’s Mother’s Day.

And so let’s go to church. Let’s be a church where we can acknowledge how difficult it is to have this day, right alongside how joyful this day can be. Let’s be a church where don’t pretend there aren’t inky depths of space between us even when we sing. Let’s be a church that fills the space between our differences with love. Because even in the most broken places, there is room for love. We can be that church.

– Becky Brooks

When we are engaged in acts of love, we humans are at our best and most resilient. The love in romance that makes us want to be better people, the love of children that makes us change our whole lives to meet their needs, the love of family that makes us drop everything to take care of them, the love of community that makes us work tirelessly with broken hearts.

Perhaps humans’ core function is love. Love leads us to observe in a much deeper way than any other emotion….

If love were the central practice of a new generation of organizers and spiritual leaders, it would have a massive impact… If the goal was to increase the love, rather than winning or dominating a constant opponent, I think we could actually imagine liberation from constant oppression. We would suddenly be seeing everything we do, everyone we meet, not through the tactical eyes of war, but through eyes of love.

We would see that there’s no such thing as a blank canvas, an empty land or a new idea — but everywhere there is complex, ancient, fertile ground full of potential….

We would understand that the strength of our movement is in the strength of our relationships, which could only be measured by their depth. Scaling up would mean going deeper, being more vulnerable and more empathetic….

– Adrienne Maree Brown

Love is the vital essence that pervades and permeates, from the center to the circumference, the graduating circles of all thought and action. Love is the talisman of human weal and woe — the open sesame to every human soul.

– Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Sermon: “Talk About Love”

I don’t know about you, but when I start thinking about “love,” just the word in the abstract, in my head I start hearing the soundtrack from the Summer before my senior year in high school. I know, love has much deeper significance than a 17 year old’s passions and heartbreaks – and at that age there were many – but it’s what comes up for me, and let’s face it – a lot of have those kind of associations. The teenage experience never completely fades, and after all, passion and heartbreak are pretty important too.

The Summer of 1989 I was a big fan of the singer-songwriter Nanci Griffith, and she’d just released a new album. I bought it the first day. A friend and I took it back to my house, where we sat on the family room floor and put the record on. The first words of the first song were, “I don’t wanna talk about love ‘Cause I’ve heard it before and it talks too loud.”

That particular song might have come into my head this week because the weather was nice and I didn’t really feel like writing a sermon. But it also may have come to mind because it echoes a kind of dismissiveness I sometime hear when we talk love, whether it’s in religion, or in life, and in Unitarian Universalism, and I knew I was going to need to address that. So maybe that’s the song going through your head, too.

But it’s telling that the other song from that Summer which has been going around and around in my head this week is Bonnie Raitt’s “Are you ready for the thing called love?” (“…Don’t come from me and you, it comes from up above. I ain’t no porcupine; take off your kid gloves. Are you ready for the thing called loooove?”)

In a way Mother’s Day is like that too. As Becky Brooks reminded us, it comes every year whether we have great relationships with our mothers or children, or we don’t. It comes whether we’re spending this afternoon at brunch, or whether we’ve had a child or a parent who died, or who has become estranged, or who was abusive, or who we are extremely close to, or who we feel kind of ambivalent about. It comes for families with two moms or two dads. It comes for trans-moms and trans-dads and drag-mothers and non-binary parents. It comes for single parents of every gender. It comes for my friend who uses the pronouns “they/mom.” (Do not try telling them that “Mom” is not a pronoun. We know what they mean.) It comes from neurodiverse mothers and mothers of neurodiverse children. It comes whether our feelings about it are joyful or painful or just incredibly complicated.

I don’t want to talk about it. Are you ready for it?

Love is a big part of what makes this day so complicated, the losses harder and the gifts more precious. Our yearning for love where it has been missing can leave an emptiness and longing. The embrace of love by those who have filled a mothering role in our lives, whatever their relation to us, and whatever the context, especially when it has been otherwise missing, makes it holy.

Love is more than an emotion. Bayard Rustin said, “love is the greatest power existing.” Now, that’s a powerful message in itself, but what’s more powerful is when he chose to say it. In 1942, on a bus from Louisville to Nashville, Rustin refused to give up his seat in the front when the driver told him this section was for Whites only. The police came, yelling and calling him – well, I think you know what they called him – but he told them, “If I sit in the back of the bus I am depriving that child” – and he pointed to a young White child – “of the knowledge that there is injustice here, which I believe it is his right to know. It is my sincere conviction that the power of love in the world is the greatest power existing. If you have a greater power, my friend, you may move me.”

They arrested him. When they beat him, he refused to resist, treating the officers with love and respect, even as they kicked him on the ground, even as onlookers begged them to stop. At the police station in Nashville, he held his head up so proudly that they told him he was crazy, that he was supposed to be scared. Rustin leaned on his sense of justice and on the love that was his compass. Listening to the police tell the DA lies about what had happened, Rustin finally had his turn. He first talked about pacifism, about his work for The Christian Century, and then turning to the events on the bus, he said to the police, “Stop me if I deviate from the truth in the least” and gently told his story with no interruptions. When he was finished, he looked the youngest policeman in the eye and said, “Did I tell the truth?” The officer hesitated. “Well,” the DA said, “You may go, Mister Rustin.” (Don’t underestimate the significance of that “Mister,” spoken in a police station in the South to a Black man in 1942.)

Rustin knew that love was more than just a feeling, more than what Martin Luther King, Jr., who he would later come to mentor, called, “sentimental bosch.” Rustin knew that love was a moral power.

Most of us haven’t been forced off a bus, persecuted and hated simply for existing, but some have come close. Just ask a drag queen in Kentucky, or a gay teacher in Florida, or any transgender child who has had to face the vitriol of those who tell them they are not who they know themselves to be. Just ask anyone who has been pulled over for driving while Black, or been told to go back where they came from, or has endured any form of racism or misogyny.

There’s a reason UUs say that we side with love, and it isn’t just that we like Martin Luther King and Gandhi, or we’re all hippies, or even that “It’s the Universalist coming out; they were always more comfortable talking about that squishy stuff than the Unitarians.”

Well, you can’t find a greater prophet of rationalism than William Ellery Channing, the minister who formed the American Unitarian Association two hundred years ago, the man who gave us the name Unitarian, and who said, “If religion be the shipwreck of understanding we cannot keep too far from it.” Channing placed love at the center of his Unitarian faith. God he said, is love, and “love is the brightest communication of divinity to the human soul.”

“What do I mean by love,” he said, “when I thus speak? Do I mean a constitutional tenderness? an instinctive sympathy? the natural and almost necessary attachment to friends and benefactors? the kindness which is inseparable from our social state and which is never wholly extinguished in the human breast? In all of these emotions of our nature I see the kind design of God; I see a beauty; I see the germ and capacity of an ever-growing charity. But they are not virtues…. The love, the benevolence which I honour as a virtue, is not the gift of nature or condition, but the growth and manifestation of the soul’s moral power. It is a spirit chosen as excellent, cherished as divine, protected with a jealous care, and especially fortified by the resistance and subjection of opposite propensities. It is the soul determining itself to break every chain of selfishness, to enlarge and to invigorate the kind affections, to identify itself with other beings, to sympathise not with a few, but all the living rational children of God, to honour others’ worth, to increase and enjoy their happiness, to partake in the universal goodness of the Creator….”

I have a few of takeaways from this. One is that even 200 years ago, people complained that “love” is too squishy a concept, or dismissed it as a nice feeling, and Channing would have none of that. A second is to wonder at his use of the term “rational children of God,” in an age when “rational” sometimes meant “White.” That’s not the main point, but it’s important to recognize the long history of racism within as well as outside our faith. Love requires honesty.

But with that aside, think about what Channing said. I know it sounds all flowery and 19th century, but think about what he said.Love is “the growth and manifestation of the soul’s moral power.” Love is what motivates us to put the needs of others ahead of our own comfort or desires. Love is what bids us to sacrifice some of our privilege so that other people may have better lives. Love is what allows us to see others as human even when we don’t understand them, and I think Channing grew in that ability himself over the course of his life and preaching. I also think the seeds of our UU statement of inherent worth and dignity are right here in these words from two centuries past. “Love is the growth and manifestation of the soul’s moral power.”

You know who gets this? Mothers. Fathers, too. All parents realize that love is more than a feeling, because the truth is there are times when we might not like our kids very much. I know it’s a horrible thing to admit, but when you haven’t had more than three hours of sleep at a time for four months, or your kid is throwing one more tantrum in one more public place, or is just being obnoxious, and is old enough to know better, you come face to face with the reality that love is not just an emotion. Emotions wax and wane. Love is the moral force that guides you to give to this other life, whatever you might be feeling in the moment.

Every time we dedicate a child in our congregation, we say these words to the parents – “There will be times when you will be called upon to sacrifice ambitions, deny yourselves pleasures, or set aside some of your own dreams so that your children may move more surely through their own lives. You accept this service to their lives, knowing that as your children grow you also will grow.” That’s a parent’s love – not just a feeling, but a moral power.

One of the deepest spiritual practices I know is to take that kind of love – the moral power that guides us – and apply it beyond our children, parents, family and friends, as broadly as we are able. It’s easier than it sounds. We don’t need the feeling of deep affection for everybody. Love is not just an emotion. When we are moved to action by the sight of another’s pain, when we can find the humanity in those with whom we are in bitter conflict, when we are motivated to work for justice and equality where people’s worth and dignity has been disrespected, we practice love. It’s at the root of work for LGBTQ equality, and the freedom to choose, and Black Lives Matter, and transgender rights, and so much more.

And sometimes love can get us through what seems impossible. There have been times when I felt myself under attack, and I wanted to bolt, or to strike back hard and treat others the way they were treating me. It wouldn’t have helped. It would have made things far worse for me and the people around me, but I’d have done it if it weren’t for love. As angry as I was on my own behalf, I didn’t stop loving those other people. I thought about the pain – maybe old pain – behind their hurtful actions, and my heart broke for them. It didn’t mean I wasn’t still angry, or that I wouldn’t do what I needed to do to protect myself and others from harm, but it did mean I could never see another person as less than human.

That’s the power of love, and that’s the moral power at the heart of Unitarian Universalism. Without it, what would our religion be? A philosophy? An intellectual exercise? Empty? Love gives us depth.

That’s the power of love, and that’s the moral power at the heart of Unitarian Universalism. Without it, what would our religion be? A philosophy? An intellectual exercise? Empty? Love gives us depth.

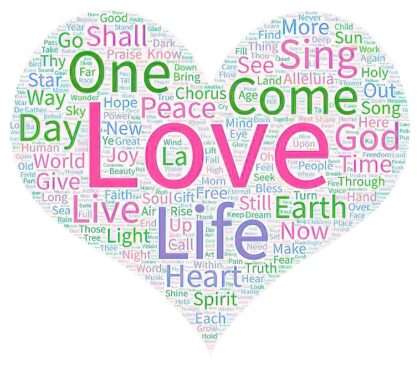

A couple of months ago, I wondered about the words of the hymns we sing each week. Every Sunday morning we spend just about as much time singing as listening to a sermon. So what we sing says a lot about Unitarian Universalism as we actually practice it, week in and week out. These are literally the words coming out of all of our mouths. Now I happen to have the text of each of our hymnals – just the lyrics – in Word documents, to pass out to people with vision disabilities. So one afternoon I copied and pasted the entire 74,000 word file of Singing the Living Tradition into an online word cloud generator. A word cloud is a picture made from the words in a text, and the more often a word is used, the bigger it will be in the cloud. If you open your order of service you’ll see an insert with the words to Love Will Guide Us on one side and word clouds from each of our hymnals on the other. The top one, shaped like a heart, is from the gray hymnal, Singing the Living Tradition, and the bottom is from the teal, Singing the Journey.

There are several big words for us – “life,” “Earth,” “heart,” – but what stands out is love. Love, by far, is the word we sing the most. It isn’t even close. We sing love over and over, and it’s not just singing. Love is part of our mission in this congregation – Grow in spirit heart and mind, love through care and community, serve beyond ourselves. It’s written into our vision statement and our covenant – three statements this congregation created and voted on over the past few years. Love is central to who we are, here in this congregation. You have said so, repeatedly.

Love isn’t in the current UU principles, at least not the word love, though it gets a mention in one of the sources, but I believe it undergirds every one of them. The inherent worth and dignity of every person, justice, equity, and compassion, the right of conscience and the use of the democratic process, even respect for the interdependent web – it’s all rooted in love. Our commitment to a free and responsible search for truth and meaning has love at the core, because it is love which motivates us to gather with those who believe differently than we do, to listen to each other and to grow together, to create community that does not depend on creeds or threats.

Love, “the growth and manifestation of the soul’s moral power…., the soul determining itself to break every chain of selfishness…, to identify itself with other beings,” love is the moral power of Unitarian Universalism. It has been true and remains true whether we amend our statement of principles and values or we keep it like it is. It’s true whether or not we ever write it down. It’s true whether we talk about love or call it something else. It’s not about what we believe, necessarily, or what we feel, necessarily, or even what we say. It’s about the way we live Unitarian Universalism in the world, in our congregation, and in our lives. It’s about the soul’s moral power.

And it’s a blessing, I believe, because it makes our lives so much better, it makes the world better, and frankly it makes our congregation much better. Maybe it’s the reason you came here, what you felt the first time you walked in the door or tuned in online.

There is love in this place. There is love here for you. Whether you were the world’s greatest mother or you struggled, whether you came here feeling ready and excited, or abandoned and afraid, whatever your color or gender identity, or sexual orientation, whether you believe in God or God talk isn’t for you, whether you talk about love or not, whether you’ve got it all together, or are hanging by a thread, there is love here for you.

Whoever you are, there is love here for you, and through you, love will grow.

May we find love in this place:

love in our hearts,

love for the broken-down,

love for the lonely,

love for those yet to feel whole,

love for those in-between,

love for those out of our reach.

May we find love, add love, and be love in this world.

– Laura Riordan Berardi