Day of Justice

by Rev. Dan Schatz

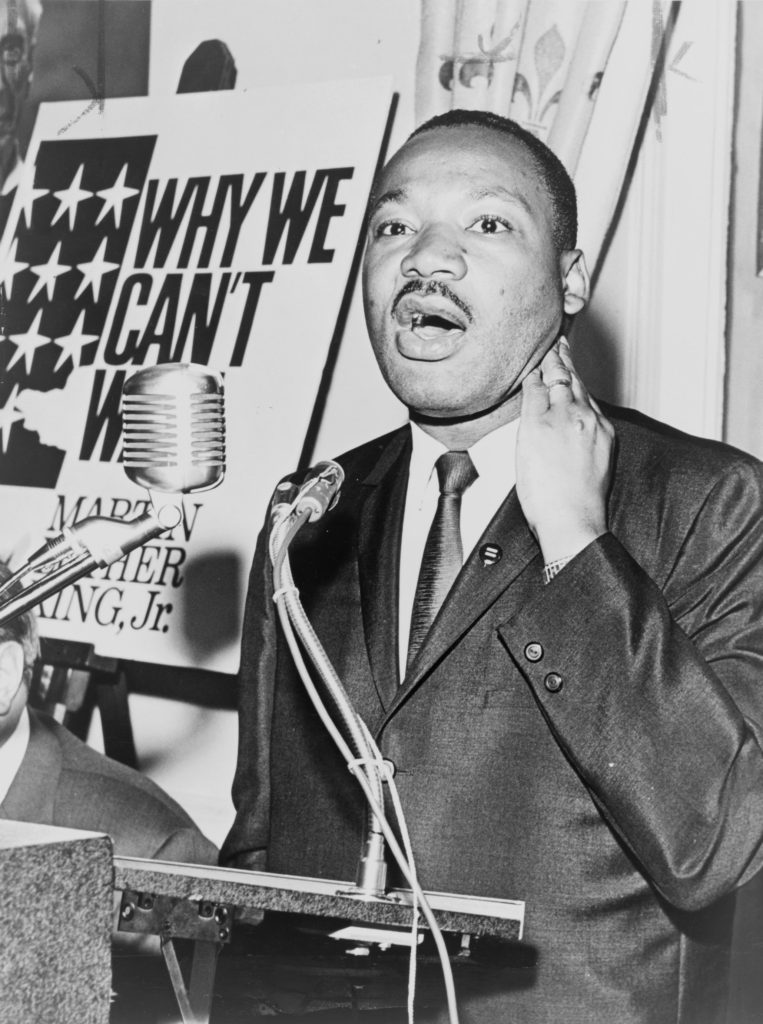

with readings from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Unitarian Congregation of West Chester

January 16, 2017

Come in to this place of memory and justice,

where the spirit enlivens and calls us forward,

transforming and renewing

with love and freedom for all.

The Words of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Courage is an inner resolution to go forward despite obstacles; cowardice is submissive surrender to circumstances. Courage breeds creativity; cowardice represses fear and is mastered by it. Cowardice asks the question, is it safe? Expediency ask the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular?

“But conscience asks the question, is it right? And there comes a time when we must take a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but one must take it because it is right.”

― The Other America

“One day the South will recognize its real heroes. They will be the James Merediths, with the noble sense of purpose that enables them to face jeering, and hostile mobs, and with the agonizing loneliness that characterizes the life of the pioneer. They will be old, oppressed, battered Negro women, symbolized in a seventy-two-year-old woman in Montgomery, Alabama, who rose up with a sense of dignity and with her people decided not to ride segregated buses, and who responded with ungrammatical profundity to one who inquired about her weariness: “My feet is tired, but my soul is rested.” They will be the young high school and college students, the young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders, courageously and nonviolently sitting in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience’s sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, and thusly carrying our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.”

― Letter from a Birmingham Jail

“Even today there still exists in the South – and in certain areas of the North – the license that our society allows to unjust officials who implement their authority in the name of justice to practice injustice against minorities. Where, in the days of slavery, social license and custom placed the unbridled power of the whip in the hands of overseers and masters, today – especially in the southern half of the nation –armies of officials are clothed in uniform, invested with authority, armed with the instruments of violence and death and conditioned to believe that they can intimidate, maim or kill Negroes with the same recklessness that once motivated the slaveowner. If one doubts this conclusion, let him search the records and find how rarely in any southern state a police officer has been punished for abusing a Negro.”

― Why We Can’t Wait

“I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

― Letter from a Birmingham Jail

“Many liberals have fallen into the trap of seeing integration in merely aesthetic terms, where a token number of Negroes adds color to a white-dominated power structure. They say, ‘Our union is integrated from top to bottom, we even have one Negro on the executive board’; or ‘our neighborhood is making great progress in integrated housing, we now have two Negro families….’

“The White liberal must see that the Negro needs not only love, but justice. It is not enough to say, ‘We love Negroes, we have many Negro friends.’ They must demand justice for Negroes. Love that does not satisfy justice is no love at all. It is merely a sentimental affection, little more than what one would have for a pet. Love at its best is justice concretized. Love… is not conditional upon one’s staying in his place or watering down his demands in order to be considered respectable….

“The white liberal must rid himself of the notion that there can be a tensionless transition from the old order of injustice to the new order of justice…. The Negro has not gained a single right in America without persistent pressure and agitation….

“Nonviolent coercion always brings tension to the surface. This tension, however, must not be seen as destructive. There is a kind of tension that is both healthy and necessary for growth. Society needs nonviolent gadflies to bring its tensions into the open and force its citizens to confront the ugliness of their prejudices and the tragedy of their racism.

“It is important for the liberal to see that the oppressed person who agitates for his rights is not the creator of tension. He merely brings out the hidden tension that is already alive….

“The white liberal must escalate his support for racial justice rather than de-escalate it…. The need for commitment is greater today than ever.”

― Where Do We Go from Here – Chaos or Community?

“One of the greatest problems of history is that the concepts of love and power are usually contrasted as polar opposites. Love is identified with a resignation of power and power with a denial of love. What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive and that love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.”

― The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Another way that you love your enemy is this: When the opportunity presents itself for you to defeat your enemy, that is the time which you must not do it. There will come a time, in many instances, when the person who hates you most, the person who has misused you most, the person who has gossiped about you most, the person who has spread false rumors about you most, there will come a time when you will have an opportunity to defeat that person. It might be in terms of a recommendation for a job; it might be in terms of helping that person to make some move in life. That’s the time you must do it. That is the meaning of love.

“In the final analysis, love is not this sentimental something that we talk about. It’s not merely an emotional something. Love is creative, understanding goodwill for all men. It is the refusal to defeat any individual. When you rise to the level of love, of its great beauty and power, you seek only to defeat evil systems. Individuals who happen to be caught up in that system, you love, but you seek to defeat the system.”

― Loving Your Enemies

“Time itself is neutral; it can be used either destructively or constructively. More and more I feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than have the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to work to be co-workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right.”

― Letter from a Birmingham Jail

“I got into Memphis. And some began… to talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers? Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!

“And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

― I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,

April 3, 1968, Memphis Tennessee

Sermon: “Day of Justice,” by Rev. Dan Schatz

A couple of years ago on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, I joined fellow clergy, members of UU congregations, and thousands of others to march through Center City Philadelphia. Maybe some of you were there on that cold January day. The speakers at the rally talked about their children, young men guilty of nothing, harassed regularly on their ways home from school under the oppressive system of stop and frisk. They spoke of the absurdity of a system which took money away from already underfunded public schools and then took local control away, too, because the schools were now “failing.” I heard the phrase “Black lives matter” over and over again, and I heard the soul singer Aja lead six thousand hands and voices in the words of Ella Baker and the music of Bernice Johnson Reagon,

“We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.

Until the killing of Black men,

Black mothers’ sons

Is as important as the killing of a White man

White mother’s sons

We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.”

The day set aside to honor the work of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. has become almost unique in the list of commemorative holidays we observe every year. We don’t often spend Presidents’ Day recounting the words of Washington or Lincoln, or perform acts of community service in their names, but tomorrow we will do exactly these things in honor of Dr. King. The Day of Service our congregation participates in has over 25 ways for people to serve, and it is just one such day, in one community in a very large country. It is stunning, when you think about it.

As important as the commemorations and Day of Service are – and they are very important – I believe we also need to honor Dr. King’s life and work through acts of justice making. As important as it is to be inspired by Dr. King’s words, we also need to allow ourselves to be challenged by them. It would be very easy for Dr. King’s legacy to be made safe and sanitized, but his message was far from safe. Every year, when we hear those stirring words from the “I have a Dream” speech about the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners sitting down together at the table of brotherhood, I wonder why we don’t also hear the words from that same speech about police brutality and economic mobility, and I can’t help but remember how much deeper Dr. King’s vision was than simple friendship between people of different backgrounds.

Dr. King’s life work was in the realm of justice, and there is more to justice than kind words and charity. Those are important, and should never be neglected, but they are not enough. Dr. King believed in a God who moved through history, depending on human hands to do the sacred work of justice making. He became a minister because he couldn’t imagine a life in which he didn’t serve society, and that is what his religion called him to do. I wonder, in this time of rising intolerance, what our Unitarian Universalist religion calls us to do for justice and for society? I wonder how we as a congregation will answer that call?

How will we work together for the great good that comes from wide diversity? How will we offer sanctuary to immigrants who now fear harassment, housing and job discrimination, and possibly deportation?

How will we support the work of racial justice, and our values of equity and compassion in human relations?

How will we defend the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people when they are under attack?

How will we support the work of environmental justice in an age of rising sea levels and climate change?

We have done a great deal already, and there is much we are just beginning to do. Last year, the members of this congregation came together to make a stand in support of Black Lives Matter. That has not always been an easy stand for congregations to take. Supporting Black Lives Matter means facing hard truths about our country and its culture, about accountability, and about the unconscious biases so many are afraid or ashamed to acknowledge.

These are difficult issues. Even the phrase “Black Lives Matter” brings feelings of discomfort to many. But as I’ve pored over Dr. King’s writings I’ve learned from him that the discomfort is something we need to sit with and pay attention to, maybe pray about if that is our practice, meditate upon, absolutely learn from, but not let deter us. I’ve learned that in the work of racial justice – White liberals like me do not get to set the terms of the conversation. It is our role and responsibility to be allies. It is our role and responsibility to set aside some of our privilege so that we can listen to the voices of those who are suffering, giving our support as they ask us to do. That’s true when we’re talking about the Black lives Matter movement, just as it is true when we’re talking about the Sanctuary movement, or the disability rights movement, or the LGBTQ movement. And it’s not like those voices are difficult to find.

Maybe our discomfort will help us move and grow – because the work of justice is not about making people comfortable; it’s about transforming society. We cannot reasonably expect to do that kind of work without being transformed ourselves.

And when it becomes uncomfortable, awkward, tense, or difficult, as inevitably happens at the edge of justice-work, this is the time to ask ourselves how will we grow – spiritually and personally – from the experience. After all, isn’t growing spiritually and allowing ourselves to be challenged in our minds and our hearts, so much of what Unitarian Universalism is about to begin with?

I promise you, if we enter this work with our minds and hearts and hands fully engaged – be it for sanctuary, or Black Lives Matter, or climate justice, or something else entirely, we will be changed. None of us can expect to remain as we were before. But again, staying the same is not what Unitarian Universalism is all about.

And the deep work of justice has rewards beyond measure. I remember a Christmas Eve at another congregation a few months after I had published a response to an anonymous letter I’d received asking me to change a sign by our roadside from “Black Lives Matter” to “All Lives Matter. After the service, a young woman came up to me. She was a high school student, a young African American I had watched grow up, though she wasn’t into youth group, so it had been awhile since I’d seen her. She told me that she had been making t-shirts for her classmates that said “Black Lives Matter,” and that her Principal had told her she should be saying “All Lives Matter.” She didn’t know what to do or to say; it felt like such a slap in her face.

When she told one of her teachers, that teacher handed her a printout of an article from the Huffington Post. She got to the end of it and looked at it again. She said, “Wait a minute. This is my church. That’s my minister.” And from that moment she knew that wherever she might go, she would find in Unitarian Universalism support for her life and her calling to do justice in the world.\

The work calls to us as well. It asks us to stand and be counted, and never to set a timetable for anybody else’s freedom. It asks us to lean in to the tension, to be the non-violent gadflies Dr. King depended upon. It asks us to educate ourselves and others. It asks us to speak the truth in love, knowing that love requires justice.

This is our day of justice – not one day, but every day – not one group’s freedom, but everybody’s freedom, not what we can get for our own needs but what we are called to seek for others. This is our call to justice, and I pray that we will continue to answer, loudly and positively, so long as we have voice.

Prayer

God of love,

Spirit of justice,

Sacredness that has no name,

Help us to breathe in peace and breathe out love.

Help us to find courage so that we may do the work of justice,

standing with those who are oppressed,

listening deeply and honoring the truths that we hear.

May we be open to the learning and growth such work engenders,

and may we be honest with others and with ourselves in our own struggles.

As we do this great and important work of justice,

may we also remember the person in front of us –

one who is going through a hard time,

one who has suffered a loss,

one who is struggling with a decision,

one who is sick or suffering.

This too is our calling – to live the promise that is love.

May we live that promise

in our care for each other,

in our care for the world,

and in our justice making this day and all days.

May love be our beacon.

Amen,

and blessed be.

Sorrow will one day turn to joy.

All that breaks the heart and oppresses the soul

will one day give place to peace and understanding,

and everyone will be free.

― Paul Robeson